Locale

HANDS IN THE WATER

MEMORIES OF A BASS LAKE

First published in Volume 14, Issue 3 of The Flyfish Journal

As a child, I was convinced the dock at our family’s lake house was the epicenter of all fish activity. My evidence was an arching mulberry tree that overhung the bank and dropped its dark-purple fruit into the water, coaxing fish to swarm in response—tiny sunfish darting busily around the rocks, bass lurking in the shade and catfish cruising the banks. Other evidence included stringers full of fish, broken lines and distant splashes echoing across the water, generally just after sunset.

My proof, however, came one slow summer day as a child, while my twin brother, older sister, mom and dad were sunning on the dock. I’d waded into the shallow water with a net, slowly dipping my toes beneath the surface and watching tiny fish dart away. The rocks were slippery from the moss, but the water was clear. I stood there for a few moments, net in hand, and slowly the tiny fish began to emerge from the depths and return to their original positions. I took my hand and began to gently wave it back and forth. The fish drifted closer. I kept waving my hand, feet steady and legs as still as a tree trunk, and those bluegills kept drifting toward my makeshift decoy until I swiped the net.

The fish were fooled and I’d confirmed my suspicion: Lake Fort Scott was the premier fishing destination in the world, or at least in southeast Kansas. It was such a flurry of piscatorial activity that you didn’t even need a rod, reel, line or hook to catch a fish. You only needed a little patience, at least one hand and a net. It was the most important discovery I’d made at the lake—which is fair because not much happens at Lake Fort Scott.

Clara “Mimi” Schwartz, the unofficial Schwartz family fishing instructor, passed away on July 28, 2021. She was able to hook a fish just about anywhere.

My dad built our house on the lake in 1991 right next to our grandparents’ place and we spent nearly every summer there learning how to fish, chasing crawdads in the shallows and wondering why largemouth bass were so damn hard to catch. Now, after more than 30 years, we’ve all talked about selling the house for more than a few reasons—upkeep, lack of time to get up there, taking advantage of a “hot” market. The conversations come up, then, for various reasons, start to fade away, particularly when we’re actually there. It can be hard to let go when you’ve been through so much in a place—and we’ve all been through plenty.

Eastern Kansas escapes the flat, corn-covered expanses many associate with the western half of the state, and small hills, dense timber and ancient farm towns emerge as you head toward Missouri. Fort Scott is one of them. Just 20 miles west of the border, it resembles a miniature Appalachia more than it does the Midwest, a snapshot of what small-town life used to be—once-beautiful homes in a state of disrepair, old trucks that run despite their appearance, and vines creeping up the sides of old grain silos—equal parts decrepit and charming. Change happens slowly in southeast Kansas, if at all.

Fort Scott’s namesake lake is perfectly nondescript, for better or worse. Tucked a few miles from town in the rolling hills and farm country, it’s small enough to drive by without ever knowing it’s there, but large enough to hide all sorts of wonders—several types of catfish, panfish, bass and more than a few fishing rods my brother and I sacrificed to the lake over the years. Unlike the reservoirs of Texas, where my family lives, the trees creep right up to the banks of the lake and the water is clear and cool for much of the year and the bass seem to soak up the moss through osmosis, resulting in beautiful, dark-green fish. At just a few hundred acres, Lake Fort Scott is an afterthought to some and a hidden gem to others. For my family, it’s always been the latter.

The Schwartz family enjoys a summer afternoon. From left to right: Kelly Schwartz, Mimi and either Nic or Steven Schwartz. As twins, they can be tough to tell apart in old photos.

My grandpa did his best to fill the role of fishing mentor, but we all knew my grandma, aka Mimi, was the real angler. She knew it too. While grandpa was the mentor in title, she was the mentor in practicality; her hands, rock-steady and rail-thin, would pull earthworms in half and she’d thread the writhing mass onto a hook.

This lake was a place of firsts for all of us, our family of five and the grandparents next door. We learned how to water ski, skip rocks, chase stray cats and find countless ways to overcome the quiet, never-ending days that came with summer. Sunday church services on the porch were a constant, my father presiding as an unofficial, but well-suited, pastor. It was also the place where I learned how to flyfish, casting from the front deck of an ancient PlayCraft pontoon boat that my dad has single-handedly kept from falling apart for the past 40 years or so. Its carpet has been updated, but the two-tone blue paint is still living squarely in the ’70s. We could’ve upgraded by now, but if Lake Fort Scott were to be represented by a watercraft, a dingy old pontoon boat does the trick nicely.

Nic and Kelly look on as their father, John, rigs up a few fishing rods on the dock. The Snoopy poles are still functional and in heavy rotation with the newest generation of grandchildren.

One of my first-ever fly casts came from the dock. I’d been working for a small-town newspaper an hour west and borrowed an ancient Orvis rod my editor had lying around from her ex-husband’s collection. She was more than happy to let it go. I casted to those same gullible bluegills in the shallows, dropping a Woolly Bugger close enough to induce a strike, and lifted a fish the size of a saucer out of the water.

More than a constant, fishing was a way of marking an occasion when there was no other way to do so. We had to punctuate life’s moments by the fish we caught, otherwise how else would we? Some days it was all we did. John Steinbeck wrote, “A time splashed with interest, wounded with tragedy, crevassed with joy—that’s the time that seems long in the memory. And this is right when you think about it. Eventlessness has no posts to drape duration on. From nothing to nothing is no time at all.”

Throw a fish or two in between those nothings and, all of a sudden, you have a memory.

From left to right: the author, Nic and Kelly celebrate a day’s catch from the family dock, ages 7 and 11, respectively.

Since 1991, we’ve created our own posts in the form of fish. There’s the catfish we caught on multiple occasions that we nicknamed “Skippy” for reasons I can’t remember. He was always there for the mulberries. There’s the walleye my brother caught when I was convinced there were no walleye in the lake. There’s the 20-pound flathead we hooked one midnight—I was terrified to reach into the pitch-black water and grab it by the jaw, but my brother wasn’t going to lose that fish, so I reached down anyway. There’s my first five-pounder on the fly, the fish that’s responsible for me reaching for a black foam popper first, every single time.

But, like any other span of time, there have to be moments “splashed with interest, wounded by tragedy.” On Aug. 8, 1994, my sister had her first seizure at the age of 9. My brother and I ran up to the top floor of the lake house to find her writhing in my parents’ laps, waiting for an ambulance to arrive. During those first few months of hospital stays across the country, countless strings of seizures and unanswered questions, my family lived inside a question mark. My brother and I stayed with family friends for a while, while our parents traversed the country looking for answers and coming up with nothing. We didn’t know what was happening, other than “Kelly is sick and we need to pray,” a common refrain for our family over the years.

One of a few Schwartz family photo collages, with pictures ranging from the early ’90s to current day. Another, similar collage features images dating back to the 1960s.

The doctors ultimately failed to offer any real solutions and slapped a diagnosis of “viral encephalitis”—a term no child, or parent for that matter, should know intimately—on Kelly’s medical file. For years, they tried new medications, new treatments, new diets, but her illness remained unmitigated. Her 9-year-old brain was permanently crippled by the violent bouts and then seizures would recede long enough for her to recognize what was happening before they reappeared in full force, knocking her back to a vegetative state. It was a chaotic and devastating cycle for her, and also for our family.

Kelly’s illness reshaped every aspect of us. We tried to return to a sense of normalcy and tried our hand at attempting family vacations. One summer, we decided to mix things up and head for sunny Orange County, all five of us, to test the waters of our new reality. It’d be our first trip together since Kelly’s diagnosis. We made it through a day at Universal Studios, visiting the Bates Motel and watching the shark from Jaws eat that poor fisherman over and over, but Kelly’s seizures descended with full force. We took a red-eye home, giving her emergency doses of valium along the way, and it was crystal clear that normal was never coming back.

With a corrugated aluminum canopy, forward casts are a little tough from the bow of the pontoon boat, but cruising along the weed beds of Lake Fort Scott is no problem at all.

From then on, vacations rarely ventured beyond the confines of the lake. It was an intimate, familiar place for all of us, which meant my brother and I could give my parents the gift of roaming free in relative safety. They spent more time taking care of Kelly, while we spent more time alone, learning the ins and outs of chasing fish. Days of eventlessness turned to days of distraction. We knew when our sister was crippled by seizures that she needed our parents’ full attention, and we needed to hold up our end of the bargain by not taking up any of it. So we fished.

In those days, largemouth bass were a mystery. Bluegill would simply swim up and eat our lure, so why wouldn’t bass do the same? A few years after the onset of Kelly’s illness, my mother, in all her infinite kindness, went to the Fort Scott Public Library and picked up a knee-high stack of Field & Stream back issues. My brother and I pored over the illustrations, hoping that bass hadn’t evolved much since the 1980s, learning terms like “Texas rig,” “spin bait” and “soft plastic” and doing our best to imagine what it all meant. We looked at the hand-drawn underwater dioramas and imagined what it’d be like for one of those dark-green torpedos to ambush our lure. That summer, the hunt began.

While Lake Fort Scott isn’t known for the size of its fish, it’s packed with plenty of largemouth that are more than happy to inhale a foam popper, the fly of choice for the author and his brother, Nic.

Every year we’d come back to the lake and every year we’d get a little bit better at piecing together the puzzle. It started to coalesce and eventually we knew how to catch them on the drop in front of weeds, induce a sip along the bottom and bounce jigs in deep water, which we then applied to flyfishing as well. Like most things in life, the idea was more difficult than the reality. They weren’t all that different from the bluegill I’d waved in with my fingers years before.

Years went by in our new reality. My brother married and had his first child. My grandfather died at the age of 103, a veteran of World War II, proud husband for more than 70 years, grandfather to six and perennially outfished by his wife.

Nic casts a bass fly toward cover on Lake Fort Scott. The twins have been fishing Lake Fort Scott since they could pick up a fishing rod, about 32 of their 34 years.

On a hot September day in 2014, my brother and I went to pick up Kelly from her group home, just a few minutes from my parents’ house, to drive her to the funeral. She hadn’t been told about grandpa yet. We stopped on the side of the road, flanked on all sides by the ocean of suburbia, and did our best to explain that he was gone—not just for a little bit, but for good. She was 29 and we were 26, but by this point we’d taken on the role of older siblings. We did our best to explain death and heaven but, almost as if she were bored with our explanations, she stopped us midsentence and said, “Yeah, I know.” Kelly didn’t need us to explain; she understood just fine.

At that moment, something shifted. Until that point, Kelly had been a wounded bird we’d all protected and cared for and fretted over. My brother and I knew we’d be her legal guardians one day. But she was still our older sister. She had things to show us, perspectives to share, and every once in a while, she’d put us back in our place. If you have a good understanding of the afterlife, what’s all the sorrow for? For once, it was her trying to understand what was wrong with us, not the other way around. We celebrated grandpa with all the joy and respect a well-loved 103-year-old deserves. To the lake we went.

A modestly sized Lake Fort Scott largemouth.

In 2016, I got married a few miles from the lake house. The morning before my wedding, we took the groomsmen out on the PlayCraft, casting fly rods to the bass we’d finally figured out how to catch. It was a warm, misty morning in early October and a series of tornadoes had worked their way across Kansas the night before. Most bass anglers would try to attribute the good fishing to barometric pressure but by now we knew how to catch them regardless. My dad conducted the wedding service, I managed to avoid a panic attack, and everything went off without a hitch. Kelly had a seizure during the reception and I remember my dad holding his 31-year-old daughter in his arms while wedding guests danced to the band playing George Harrison’s “If Not For You.” His face contained sadness and joy. We still remember it as a good day.

Kelly had her last seizure on Dec. 8, 2016. My family’s prayers for healing had finally been answered with a resounding no, and after 31 years she was buried near my grandfather in Fort Scott National Cemetery, next to the space reserved for my parents.

You’ve got to cut your teeth somewhere and the Schwartz children learned (and still learn) on these Duck Tales and Snoopy Zebcos.

No one fished the day of the funeral. It was a cold morning. Leaves swirled around the graves in the gusty winds, dancing across the low hills of the ancient farm country. I assume we spent the rest of that afternoon by the fireplace, but I can’t recall anything specific, and I’m sure others in my family can’t either. I just know it was cold and gray and it was the only day I ever wore that department-store peacoat picked up just for the occasion. In the space of two years, we’d added two graves to the same cemetery and, in just a few more, we’d add another with my grandmother’s passing. We headed back in silence to the house that sits on the banks of Lake Fort Scott, unsure about what to do or what to say, other than, “Let’s head home.”

A few days later, I walked down to the dock to cast into the frigid water of the lake. We’d learned from all those bass magazines that even on the coldest days you can get a fish to bite every now and then by giving the fly a bit of play along the bottom. I cast, spraying ice-cold droplets on the back of my head, and let the line sink to the bottom, twitching it lightly on the retrieve. There were no bites, no movement, no fish. Maybe those back issues of Field & Stream weren’t worth a damn after all—I knew it’d be months before we caught anything from the lake.

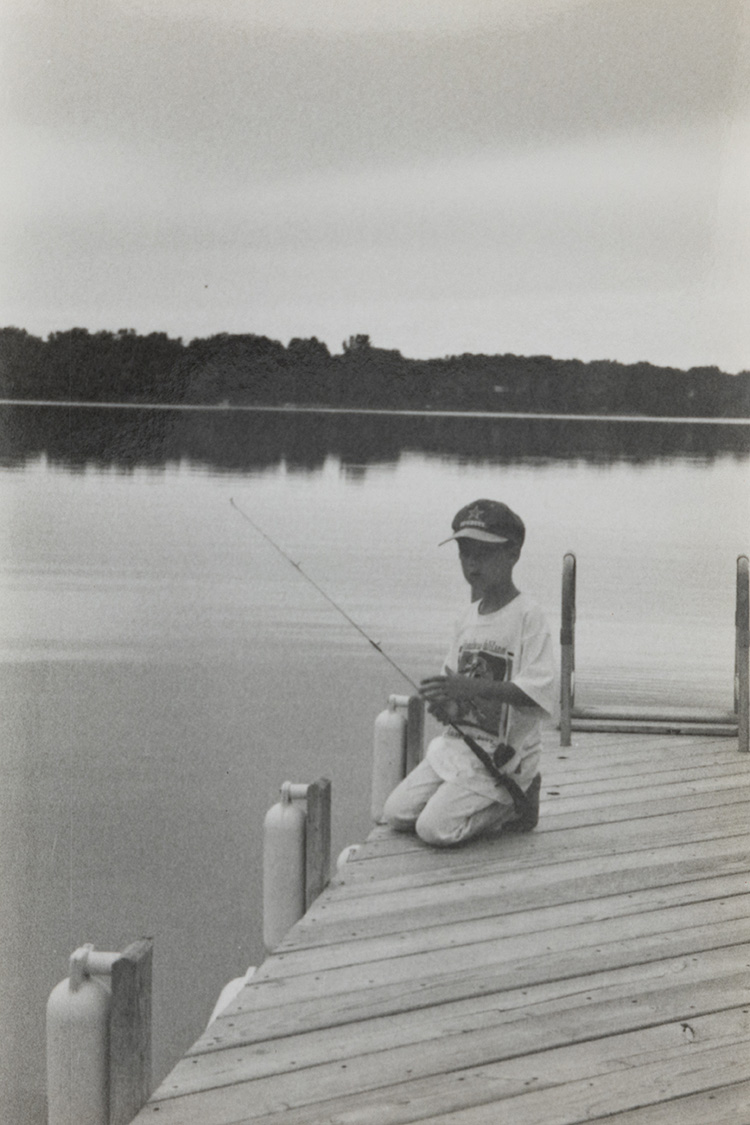

The author waits patiently for a bite. This photo was taken a few years after his sister’s diagnosis.

Nowadays, there are a few different hues to our trips to Lake Fort Scott. The Schwartz section of the Fort Scott National Cemetery has grown over the years, and my parents don’t seem fazed by the fact that they already have a spot reserved next to my sister, just down from Clara and Kenneth Schwartz, her proud grandparents. In their defense, it’s a beautiful place.

A few years after Kelly’s passing, we stopped at the graves to say hello to her, Mimi and grandpa, the same as we always do. It was a sunny, mild Kansas day with just a bit of a breeze. My brother and I stood in front of Kelly’s grave with our parents, while our own kids ran around screaming and laughing, unaware they were playing on hallowed ground, and my dad started to read one of his favorite Bible verses, 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18, but couldn’t get the words out through his tears. He asked me to finish. The passage concluded, “Therefore encourage one another with these words,” and we drove down National Avenue, toward Main Street, and eventually down the road to the lake. We spent the day on the dock, threading worms onto hooks for our children, the same way Mimi had for us, dropping the hook down for the bluegill that seemed to be as gullible as they ever were. My nephew picked up his first-ever fish with pride, suspending it over the dock with an elated smile, while my children looked on with jealousy. At just 3 years old, we’re fairly certain we have an angler on our hands.

The author, at 5 or 6, holds a stringer of channel cats and panfish.

The whole family walked back from the dock after fishing to eat lunch and enjoy some small-town radio on the deck. On the first floor, hundreds of photos are on the wall—of my grandparents helping us fillet fish, ancient snapshots from when my dad still had hair, my 8-year-old sister diving into the lake with perfect form, frozen in time. After Aug. 8, 1994, the photos are a bit more sparse. There are still fish photos and smiling faces, just not quite as many, and much like the rings of a tree, you can discern periods of joy and sadness by the density of photos on the wall.

New photos are coming. With each summer season, images of children holding up fish with proud looks on their faces are already starting to pile up and I’m sure they’ll eventually make it to the wall along with the old memories. My brother and I, now three years older than my sister ever was, have six kids between us, and none of them like to put a worm on the hook and they certainly can’t cast a fly rod. But, when we hand them a rod and tell them to “reel, reel, reel,” their faces fill with joy and they seem to believe they were in control the entire time. I haven’t told them that if they wade slowly into the shallows, stand as still as a tree, and wave their hand back and forth in the water, they don’t even need a rod and reel to catch fish. I’m sure they’ll figure it out on their own.

Nic releases a largemouth bass caught during summer 2022. On warm days, the topwater bite heats up during the first hour of daylight.

It would be too tidy to say this lake defines our family and neither does Kelly’s long sickness. We don’t have much of a say about what happens to us, but we’re defined by how we respond. For more than 30 years, we’ve responded in plenty of ways—through tears, prayer, smiles and silence—but we’ve always come back. We return to memories of joy and sadness, memories of pain, but we choose to return regardless. It is our post to drape duration upon. The cross-section. The record. If Lake Fort Scott is anything, it’s a reminder, and those are worth holding onto. Sure, we still talk about selling the place from time to time, but we just can’t seem to let it go. It seems like the market is slowing down anyway. Maybe next year.